PENUMATCHA

CULTURAL STUDY OF A VILLAGE IN RURAL INDIA

Understanding systems and identifying gaps

A Cultural Study of Rural Systems

Penumatcha is a Village in Pamidimukkala Mandal in Krishna District of Andhra Pradesh State, India. It houses around 500 families. As part of a curriculum module we were to visit the village and undertake a study on the cultural and societal practices there, document these, and subsequently identify gaps and optionally, propose solutions that could be implemented.

Through my interaction with the community, I learned of the persistent grip the caste system has in rural India despite constitutional declarations that oppose it. This ignited my passion to delve into societal frameworks. I spent the remaining weeks within the tiny settlement located away from the main village only connected by a road constructed not too long ago.

Upon exploring communication, architecture, and rural systems, I found myself drawn to the realms of sociology, ecology, and economics. It was fascinating to uncover the nuances missed when attention was trained on components rather than the overarching structures and networks influencing them.

For instance, it was evident that there were limited education and employment prospects but when I took a step back and tried to understand why, I could see a different picture. The issues started with limited accessibility to resources, and this was what I aimed to overcome eventually through my proposed solution.

As I delved deeper into the dynamics of systems, the intricate connections between various elements became increasingly apparent. This study of systems fascinated me, with its diverse range of fields—encompassing both the abstract and the tangible.

We were given the city hall to stay in for the duration of our visit. It was a double story structure with an open layout, ideal for hosting village festivities. It put us conveniently at what seemed to be the centre of the village. On the first day of exploring the structure and visiting families around it seemed to be a close knit agrarian society with modestly built brick and mortar houses and medium sized households.

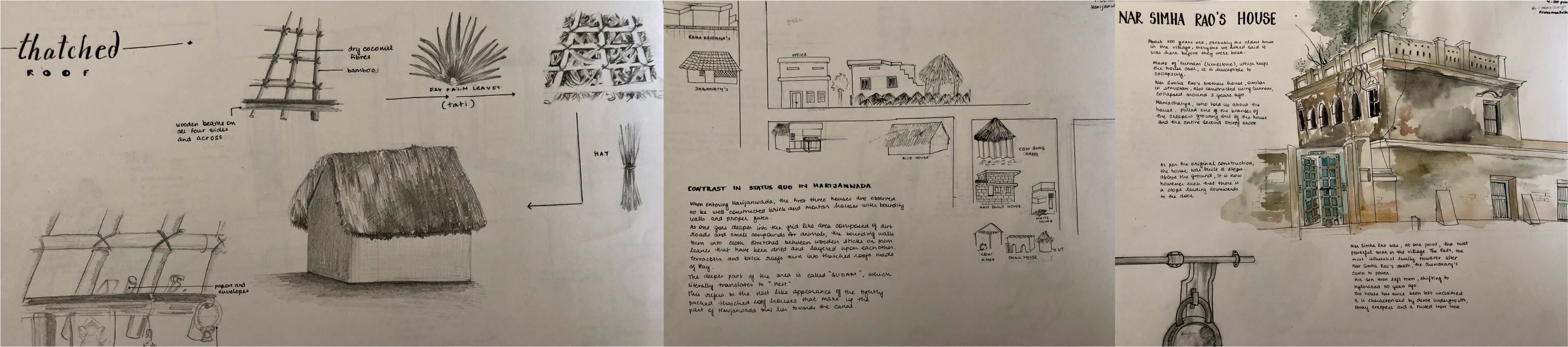

It was only a few days later that I followed a poorly built road, some one and half kilometres in length that I came across another settlement. In stark contrast to the village I’d left behind, the houses here had thatched roofs and unpaved paths. Cows sat on the dirt road, a small tea shop housed a significant crowd of visitors. A church bell ringing led me to a small Catholic Church. Here I met the priest, he told me he was one of the few people in the village who could speak English and would be happy to answer all my questions. The area was called ‘Harijanwara’—the name itself translating to ‘area where lower caste people live’. He told me about how this settlement had been completely isolated from the main village until a few years ago, with no road connecting the two. They weren’t even allowed to use water from the village’s water repository. The population mostly worked in farms as labourers or in the houses of the higher caste families, performing menial tasks.

I consolidated my learnings into a comprehensive document of the class and caste structures that existed in the village. The structure’s origins in faith and religion, their influences, as well as their manifestations in the lives of the youth of the community. Although geographically proximate, the younger generation of the more affluent— and higher caste—areas were able to study in larger cities or even overseas. However, the youth belonging to disadvantaged groups would receive a meagre education—which they would often not end up completing—instead they burdened by engaging in labour or part time work to make ends meet.

To address these gaps, I proposed setting up a system—to be implemented after the sixth grade—where learning and earning could be organised within a program that allowed for the simultaneous action of both. For later years, a platform could be provided that looks to make accessible state and centre sponsored support for further education and greater opportunities. There exist a large volume of government funded schemes and scholarships intended for the underprivileged but little access and awareness about the same. Information about this support exists on various websites belonging to different ministerial branches. For the rural population that is not familiar with the internet it can be infinitely challenging to navigate across multiple sites.

My solution looked to consolidate the numerous opportunities available onto a single platform. The platform itself was designed to be simple to navigate from a Ux/Ui perspective along with having language support so that it could cater to the exhaustive language diversity in rural India.